#44: Out of My Mind (US) (1967) – John

Brunner (3.5/5)

I believe I’m on my thirty-fourth Brunner book.

Reading Out of My Mind was spurred by Joachim Boaz’s comment

on Brunner short story “Nobody Axed You” (1965). He loved the story and it

reminded me how versatile (…or unpredictable) a writer Brunner used to me. He

had some obviously brilliant “wheat” but also had the inevitable

“chaff” mixed among it all. Out of My Mind, thankfully, doesn’t contain

any of the chaff; nor does it, however, show any great ambition or artistry

that Brunner later exhibited along the lines of Stand on Zanzibar (1968)

or The Sheep Look Up (1972). The stories have an aura of whim exuded by

the author—many of them aren’t serious in nature, yet are cleverly based on the

kernel of an idea that Brunner ran with. This doesn’t always translate well as

it feels just like that: this is my seed of my idea (which may be good or bad,

depending on the reader) and this is the roughly textured chaff that surrounds

it (sometimes good, sometimes bad, too). “Round Trip” (1959), one of Brunner’s early

stories, may be simple at first glance but has a few depths of thought: one of

science, one of humanity, one of alternative worlds, one of whim, and another

of romance. In between these two sides of the spectrum, Brunner pens some

stories that either evoke nods, smiles, or the raise of one or both eyebrows.

#45: The Wild Shore (1984) – Kim

Stanley Robinson (4/5)

The 1980s hosted a spat of

post-apocalyptic novels: Ridley Walker (1980), War Day (1984), The

Postman (1986), Pilgrimage to Hell (1986), The Sea and the Summer

(1987), Swan Song (1987), The Last Ship (1988). Tucked among them

is Robinson’s The Wild Shore, which is part of his Orange County

non-sequential trilogy. This novel—and the trilogy, in fact—doesn’t receive

much praise from SF fans as it precedes his much more famous Mars trilogy (1993-1996).

In 2047, decades after the Soviets

detonated several thousand neutron bombs in America

#46: The Gold Coast (1988) – Kim

Stanley Robinson (3.5/5)

I read two of the Orange County books

in 2007 but had trouble getting a hold of the middle of the three: The Gold

Coast. I found a hardback copy of the novel at a local library book sale,

so it’s remained on my shelves for a while. When I drew the book to be read, I

decided to read the trilogy in chronological order. It provided some decent airport

and airline reading.

Youthful angst and the need to be

heard—in everyday physical acts and in occasional clandestine acts—bubbles up

through the hormones. Much of California and America has given way to rampant

capitalism and development: so-called progress in a mild dystopia. Outlets for

the naïve angst begin to take on a more destructive note as Jim is drawn to the

casual bombing of American’s military industrial machine. He’s conflicted,

however, as his own father is a high-level engineer for one such company. As

Jim faces a complicated series of alliances to friends, Jim’s father knows one

thing: the feasibility and physics of his company’s projects. Detail-oriented,

he can peer deeply in to any plausibility of laser systems or guidance

packages, but his boss only wants results, contracts, and money; these very

things, however, become difficult to procure as the government is at their own

game of cat and mouse. Jim’s dad plays the mouse at both the company and

government level, but he’s soon to be targeted on a personal level by his own

son. Amid the crazy bureaucracy at the professional level and lavish,

free-wheeling lifestyle of the youth, there’s the recurring character of Tom to

embody the ambiance of his time. Tom sits in the psych ward forgotten by his

family for the most part, rambling on with stories that digress.

#47: Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and

His Years of Pilgrimage (2013/2014) – Haruki Murakami (4/5)

I like Murakami’s work, but I’m not a

frequent reader. I read Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World

(1985/1991) in 2009 and later A Wild Sheep Chase (1982/1989) in 2011. Most

often in Thailand , his books

about 50% more expensive than other novels, so I was delighted to find a

beautiful copy of one of his latest novels in a Florida

In high school, a mere coincidence

spawned a lasting friendship: Tsukuru Tazaki and four other volunteers clicked

while on assignment and soon became inseparable; however, Tsukuru always felt a

little excludes as the four others had colors in their surnames, thereby

rendering him, in his own opinion, colorless. When he departed from Nagoya to

attend university in Tokyo, Tsukuru still returned to frolic in the friendship

that seemed eternal… until the day they banished him from the five-some without

any explanation. He accepted this banishment, returned to Tokyo, and came close

to suicide as he denied himself all good things. A small realization quickly

turns his life around: he exercises, studies, graduates, and gets the job of

his dreams—designed railway stations. Relationships still come and go, but the

perfection of his once five-some still haunts him and he never received an

explanation.

He meets Sara, whom he becomes

increasingly attracted to in body and spirit, but it’s her mind that comes

between them. In order for their relationship to progress, she suggests that he

revisit his old friends in order to understand his banishment. Thus, he learns

of lies and regret, but he shares this regret:

One heart is not connected through harmony alone.

They are, instead, linked deeply through their wounds. Pain linked to pain,

fragility to fragility. There is no silence without a cry of grief, no

forgiveness without bloodshed, no acceptance without a passage through acute

loss. That is what lies at the root of true harmony. (322)

This web of lies and regret also impinges

upon his relationship with Sara, unknowingly to her. His pain folds upon

itself, he sees himself as an island that can never know contact with another

landmass. He was once bitten by the openness of his heart, and now he’s bitten

again—does he whither again in suicidal thoughts or does he push ahead?

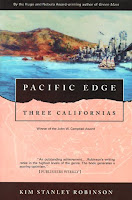

#48: Pacific Edge (1990) – Kim

Stanley Robinson (3/5)

This was the first book in which I fell

in love with one of the characters, was enchanted when the protagonist won her

over… and I was genuinely heartbroken when they broke up. That relationship had

always burned in my mind so brightly that I had completely forgotten the rest

of the story. When I picked this novel up again, I was ready for the

rollercoaster of love, so I could focus on the rest of the novel, which didn’t

ring many bells nor win many points.

Kevin’s in his thirties. He’s

uninvolved in love but very much involved in his renovation business, the

softball league, and has recently become involved in his township’s political

arena. While his business may continue its steady productive pace, the other

three important aspects of his life are soon to change because of a girl and

another boy: Ramona and Alfredo. The two long-time lovers have recently split

and Kevin is quick to catch the rebound. He swims in all of her attention, he

dances in the shower of shared time, he basks in her every word:

What do you talk about when you’re falling in love?

It doesn’t matter. All questions are, Who are you? How do you think? Are you like

me? Will you love me? And all answers are, I am this, like this. I am like you.

I like you. (134)

At the same time, Alfredo—who is the

acting mayor—tries to pass an item through a boring meeting, but Kevin is quick

to call him out on its importance. Meanwhile, the softball season starts and

Kevin is off to a great start by batting a thousand. His batting streak is his

only charm as his other two affairs become entrenched with outside influences:

Ramona, the once raven beauty and tinder of his heart, becomes distant with

him; Alfredo keeps pushing his agenda while Kevin stands for the fight. All

Kevin wants is a steady life for his community, but the future politics of California

Amid the turbulent life of Kevin, his

grandfather Tom is late in his own life but also rides the choppy seas of what

life has to offer. Love doesn’t grey like hair as Tom unexpectedly finds his

spark in life, with which come options: stay to see out Kevin’s tribulations or

set out into the world to see what comes.

#49: Ship of Strangers (1978) – Bob

Shaw (2.5/5)

My seventh Shaw… and I have no idea

what to make of it. It’s presented in chapters, so it’s a novel; yet there are

five distinct stories, so it’s a stitch-up; yet not all of the stories had been

individually published. The stories don’t interrelate, nor are they sequential.

It’s not a novel, a stitch-up, or a collection…it’s poor editing and

publishing, I think.

The Sarafand was made to venture

to the untouched planets of the ever-expanding Bubble of human exploration.

Aboard are members of Cartographical Service crewmen who see the lucrative

short-term job stint amid the perpetual boredom of visiting dead, arid planets

for the sake of science. Dave Surgenor, however, is someone who actually made a

career of the service and he has stories to tell, which is compiled is this

novel/stitch-up/collection: (1) An alien mimics the shape of their six scouts

ships and AESOP—the artificial intelligence aboard the mother ship—must figure

a way to distinguish among the real scouts; (2) The men’s private nighttime

fantasies spill into their own relationships as a trouble maker begins to share

the tape around, with emotion, lust, connotation and all. (3) Mike Targett is a

bit of a gambler who bases decisions on odds alone, but when he takes a chance

to investigate some metallic cylinders on a new planet, he gets much more than

he bargained for. (4) Mirages upon another deserted planer spur a full-blown

military investigation, but a kidnapping of an alien woman turns into a

single-exit escape from a jungle. (5) An error in a beta-space jump causes the

ship to become stranded millions of light-years away in a system that seems to

be collapsing upon itself, yet the crew to seem to be folded upon themselves

under the added pressure of having of a woman aboard and having no way to

return home.

These stories have the same whim at

George O. Smith’s Venus Equilateral series of stories: There’s a group of men

on an isolated post who encounter strange problems in a world of order yet try

to outwit the ensuing chaos. As the book is dedicated to A.E. van Vogt, is also

rings of the latter’s The Voyage of the Space Beagle novel/collection.

But the parallelisms aren’t true enough or significant enough to begin to

compare the two.