Sociological impetus concedes to plot twists (3/5)

This was Boyd's first novel back in 1968 and part of a trilogy, of

sorts, based on classic myths. Myths have never been my forté and nearly

all of the novels which heavily rely on myth connotation are lost on me

(Delany's Einstein Intersection to name one). With novels like these, I

try to adjust the plot's pressure from the pillar of mythology to the

load bearing pillar of science fiction. Sometimes the load is just too

much (i.e. Einstein Intersection) and the house of a novel's plot comes

crashing down with me shoulder-shrugging in a carefree yet disappointed

manner. Thankfully, The Last Starship of Earth wasn't overladen with

obvious mythology to topple the novel... Boyd's inexperience was enough

to do that.

Rear cover synopsis:

"In the futuristic society

that serves as the setting for this elegantly chilling novel, the State

decides whole one will choose as one's mate. In any case, professional

boundaries cannot be crossed, and thus the young mathematician Haldane

IV cannot fall in love with or marry the girl of his choice, the poet

Helix. But as the young couple studies ever more closely the long-hidden

poems of Fairweather I, whose work years before had completely altered

the whole nature of society and who is universally acknowledged to

greatest mathematician since Einstein, they realize the verses hold

important messages for them--and for the world. What, for example, does

this couplet mean?

That he who loses wins the race,...

That parallel lines must meet in space.

Even as they ponder, they know that the price, if they are caught, is exile to the planet of Hell."

Welcome

to the prefecture of California, part of the Union of North America,

itself part of the World State. The triune State is governed by the

Three Weird Sisters, "an agglomeration of sociology, psychology, and

priests." (52) Where the sociologists and psychologists are concerned

about the legality of the State, the Church's main concern is its

morality; the psychologists take the broad view and monitor the police

activity while sociologists are the administrators and tackle the

judiciary side of the law. The population of the earth is divided

between the proletariats as "insensate brutes" (136) and professionals

as "sheep" (136) to the powers of State.

The professionals seem

to be classified by their colleges where prefix "A" stands are ART,

prefix "M" stands for MATHEMATICS, and prefix "C" stands for

CRIMINOLOGY. Other professions are experienced but the classification

seems to be a simple dystopian tag to adhere to the two victims of its

own society: Haldane IV (M-5, 138270, 2/10/46) falls in love with the

idea of and the ideals of Helix, A-7, 148261. 13/15/47) (I believe the

latter numbers refer to their birthdays in regards to the rather

confusing 13-month Hebrew Calendar). Each professional classification is

mated within its own college, the mate chosen for their genetic synergy

in order to produce a greater knowledge-based professional class to

drive forward the specific needs of the State, where the proletariats

act as general means laborers.

On one fateful day, Haldane was

meant to go to the science museum but ended up crossing paths with Helix

at the art gallery. The mathematician is intrigued by a facet of the

legend of the greatest mathematician to even live that he never knew

about--the man also wrote poetry. Helix quotes some poetry by the legend

and Haldane never looks back twice. The two clandestinely meet to

exchange notes of the subject to ascertain what Fairweather was pointing

at with his dichotomous poetry. Haldane's roommate's loaning of his

parent's apartment is perfectly suited for these trysts and for his

weekly visitations to his father's house.

Fairweather was

noteworthy for his contributions to light-speed travel, which allowed

ships to traverse space and colonize stars. However, the State was

against such an expansion and the trips were limited to the planet Hell,

a planet shrouded in propaganda as being desolate, frozen, and four

million light-years away in the Cygnus system. One more contribution

Fairweather made to society was his invention of the electronic pope, a

supercomputer which has the last word on any sentencing done by the

State's courts.

The non-physical relationship between Haldane and

Helix borders on amorous but their social conditioning is so strong

that only a special circumstance (i.e. plot twist) can force the two to a

more physical situation. The relationship develops and ends with yet

another hasty special circumstance (i.e. predictable plot twist).

Thereafter, Haldane spends his time in jail with his lawyer being

prepped for his trial against the World State, which calls for

subversion against professional all three of the "Weird Sister" fields:

sociology, psychology, and The Church. The trial ends with Haldane

unsuspectingly given the worst sentence possible.

Witnessing the

budding relationship of Haldane and Helix amid the social restrictions

imposed by the State was a small spectacle in itself. The technocracy of

genetic pairing is familiar territory for science fiction readers yet

the entrapment is a fairly old hook (i.e. Yevgeny Zamyatin's novel We).

Up until the point of the back-to-back plot twists, the book was on a

4.5 mean average, with swathes of sociological implications and heady

passages of love yet to be fulfilled. Call me a hopeless romantic, but

the combination of the two was an opiate for me.

Then... duhn

duhn duhn, the suspenseful soundtrack of an ill attempt at a natural

plot twist, which Boyd half-way failed at. I had faith in this unknown

author at pulling off the dual plot twists as I had already invested my

faith in the first half of the novel. My trust remained strong even

through the THIRD plot twists, when I met the scenario with much

skepticism and narrowed eyes of disbelief. But when Boyd played his time

travel card, I immediately knew that Boyd made the most critical error

any author could perpetrate: don't write a story you don't have an

ending for. I would usually use "deus ex machina" to describe the sudden

event, but this came flying straight out of his rusty bullet hole.

Like

the mention of the Hebrew Calendar above and the unmentioned time

travel stint with Jesus and the Wandering Jew (oops), there's a more

latent judeo-christian underpinning beneath the novel. One lingering

questions which a social theologian may want to tackle after reading

this novel is, How has the Church affected the course of the sciences of

sociology and psychology? It's my final opinion that the years of

mention (1850-1966) are of an alternative history. Some historical names

of mention (A. Lincoln's "Johannesburg Address" isn't Abraham Lincoln's

"Gettysburg Address") are altered and point to the alternative history

origin.

While most of the historical and mythological portions

were lost on me (neither a historian or mythologist, but acquiring the

temporary persona of a mathematician), the sociological implications

affecting the amorous couple are a highlight... but after the plot

twists the wait for the conclusion is all downhill if you subtract the

details concerning the government and its history. I already own the

second book of the trilogy, The Pollinators of Eden, and glance at it hesitantly. As for book three, The Rakehells of Heaven... I release of ominous sigh of near future acquaintance.

Sci-Fi Reviews with Tyrannical Tirades, Vague Vexations, and Palatial Praises

Showing posts with label time travel. Show all posts

Showing posts with label time travel. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 5, 2012

Friday, April 6, 2012

1968: Hawksbill Station (Silverberg, Robert)

Silverberg's BEST... which doesn't say much (3/5)

I've never liked Silverberg.

Regarding his novels:

The Alien Years (1998)... hated it.

The World Inside (1971)... hated it.

Those Who Watch (1967)... hated that, too.

Regarding his short stories:

The Red Blaze is the Morning in the New Legends Anthology (1995)... didn't care for it.

Hot Times in Magma City in the Year's Best SF (1995)... didn't care for it.

The Sixth Palace in Deep Space: 2 (1973)... didn't care for that, either.

So, while I'm able to stomach his short stories to a small degree, I've hated every Silverberg novel I've touched. To say "Hawksbill Station is THE BEST Silverberg ever produced!" is not doing the novel any favors. I've tried to like Silverberg's previous novels and stories, but I always end up disliking them. The same goes for Hawksbill Station... with plenty of praise doused upon it by Joachim Boaz, I was finally stricken with guilt at my distaste for Silverberg so I paid $2.50 for the book and read it. This one is for you, fellow blogger extraordinaire.

Rear cover synopsis:

"Exiled to an unborn Earth. They had fought a life-crushing 21st century dictatorship, and now they were witness to the dawn of life itself. Bitter witnesses. For they were political prisoners, exiled forever behind a billion year-high wall of Time--sent "one way" to the grey slab shorelines of a barren Earth before life had begun its long climb from the sea to the stars. A lifeless world was their prison, and there was no way back. And then one day the stranger came..."

In the solemn year of 1984 when the constitutional crisis ended with the syndicalist capitalists takeover ("McKinley capitalism and Roosevelt socialism" [69]), dissent sprung up in both mild forms and extremist forms. The protagonist Barrett was one of the milder mannered attendees, only attending the meeting to meet the girls. With enough time dedicated to the movement, Barrett eventually dedicated himself to the dissent. When his sleazy tramp-cum-girlfriend is arrested and unheard from in 1994, Barrett continued his mild dissent, albeit at a higher level with more responsibilities, against the undemocratic government until 2006, when he was arrested, detained, and interrogated. His life then on became dedicated not to dissent, but to living life in a barren landscape where only insanity and slow death are the enemies.

In a rather generically scripted future with automatic cars, 3-D television, supersonic air transport, population control, weather control, a Mars colony, and a lunar resort, the famous mathematician named Hawksbill has created a time machine (in operation since 2004). However, this machine is only reported to be a one-way trip... and what better way to use a time machine than to simply send political prisoners a billions years in the past to the late Cambrian era where troglodytes reign the seas and the prisoners can do no harm to the evolutionary ladder:

"The government was too civilized to put men to death for subversive activities, and too cowardly to let them remain alive and at large. The compromise was the living death of Hawksbill Station. A billion years of impassable time was suitable insulation even for the more nihilistic ideas." (36)

Come to the year 2029 and the population of the primordial prison stands at one hundred forty with one-third of the prisoners succumbing to their personal psychoses. Barrett has become the leader of the chronologically desolate gulag, one who organizes men to scout for mis-shipped crates of food and materials. Losing the full mobility of his legs due to an avalanche, Barrett has become more steadfast in his hopes for the Cambrian colony, a desire which supplants his treasonous aim of governmental reform. After a six-month absence of new prisoner arrivals, a stranger arrives at the camp. A self-pronounced economist with little more to say than a simple nod and a notably empty reservoir of knowledge regarding economics and political resistance, little warning signs are piquing the accusatory eye of Barrett.

Hawksbill Station has a very similar theme to Brian Aldiss's Cryptozoic, where Silverberg's was published in 1968, Aldiss's was published in 1967. Silverberg's novella Hawksbill Station was published in August of 1967 while Aldiss's was published in October. Which author was the first to pen the idea of a totalitarian government with time travel to primordial earth (Silverberg = late Cambrian / Aldiss = pre-Cambrian)? There are obvious similarities but also drastic differences.

There are two parts to this story which capture my imagination: the penal servitude in the desolate past (draw comparisons to Dostoevsky's Memoirs from the House of the Dead or Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago) and the form of government Silverberg calls syndicalist capitalism (as a registered Socialist, of course it would interest me). However, neither are described to a great degree and merely serve as a backdrop for the existence of temporally distant political gulag. Exactly WHY this sort of prison is BEST for the prisoners is left untouched (besides the single paragraph explanation above). And the descriptions of the barren lands of the late Cambrian period are glanced over, mentioning some soil here, lots of rock everywhere, and the expansive ocean just over there.

The actual Hawksbill Station plays second fiddle to the tribulations of Barrett. The novel alternates chapters from life at the Station and the rise of Barrett's career as a dissident. His shallow relationship with his girlfriend is a mere footnote of interest, as all female characters in Silverberg novels tend to be. Barrett's almost feigning interest in the revolution doesn't draw him out to be the powerful type, but his ability to handle interrogation, detention, ans sensory deprivation are admirable. Regardless of this, he is still sent back in time to live the remainder of his life on the expansive flats of volcanic rock, a home which he will reign as king over troglodytes and treasonous male revolutionary castaways.

A minor gripe in Hawksbill but my main gripe with the author (but noteworthy because of its recurring nature in everything Silverberg has penned) is his treatment of women as characters... or as cows: things to name and forget about minutes later, or as objects: things to place in the plot as mentions of rape (three times) and breasts (four times) can be wantonly written into the story (to garner interest from teenage boys?), or as a catalyst for excitement: pheromone-laden hussies to give climax to the plot (and conveniently, to the men, too). Call it his spice to every plot or his twist to every story, but it's the main reason I don't willingly read ANY Silverberg. Again, to say that Hawksbill is the BEST thing Silverberg has ever written is to say that everything else he has written in on par with or below a three-star rating, in my opinion.

With my gripe complete and my review of Hawksbill finalized, I can put to rest your (pointing the finger) one hope of turning me into a Silverberg fan. Sorry... but you have to admit that the plot synopsis I provided it quite good!

I've never liked Silverberg.

Regarding his novels:

The Alien Years (1998)... hated it.

The World Inside (1971)... hated it.

Those Who Watch (1967)... hated that, too.

Regarding his short stories:

The Red Blaze is the Morning in the New Legends Anthology (1995)... didn't care for it.

Hot Times in Magma City in the Year's Best SF (1995)... didn't care for it.

The Sixth Palace in Deep Space: 2 (1973)... didn't care for that, either.

So, while I'm able to stomach his short stories to a small degree, I've hated every Silverberg novel I've touched. To say "Hawksbill Station is THE BEST Silverberg ever produced!" is not doing the novel any favors. I've tried to like Silverberg's previous novels and stories, but I always end up disliking them. The same goes for Hawksbill Station... with plenty of praise doused upon it by Joachim Boaz, I was finally stricken with guilt at my distaste for Silverberg so I paid $2.50 for the book and read it. This one is for you, fellow blogger extraordinaire.

Rear cover synopsis:

"Exiled to an unborn Earth. They had fought a life-crushing 21st century dictatorship, and now they were witness to the dawn of life itself. Bitter witnesses. For they were political prisoners, exiled forever behind a billion year-high wall of Time--sent "one way" to the grey slab shorelines of a barren Earth before life had begun its long climb from the sea to the stars. A lifeless world was their prison, and there was no way back. And then one day the stranger came..."

In the solemn year of 1984 when the constitutional crisis ended with the syndicalist capitalists takeover ("McKinley capitalism and Roosevelt socialism" [69]), dissent sprung up in both mild forms and extremist forms. The protagonist Barrett was one of the milder mannered attendees, only attending the meeting to meet the girls. With enough time dedicated to the movement, Barrett eventually dedicated himself to the dissent. When his sleazy tramp-cum-girlfriend is arrested and unheard from in 1994, Barrett continued his mild dissent, albeit at a higher level with more responsibilities, against the undemocratic government until 2006, when he was arrested, detained, and interrogated. His life then on became dedicated not to dissent, but to living life in a barren landscape where only insanity and slow death are the enemies.

In a rather generically scripted future with automatic cars, 3-D television, supersonic air transport, population control, weather control, a Mars colony, and a lunar resort, the famous mathematician named Hawksbill has created a time machine (in operation since 2004). However, this machine is only reported to be a one-way trip... and what better way to use a time machine than to simply send political prisoners a billions years in the past to the late Cambrian era where troglodytes reign the seas and the prisoners can do no harm to the evolutionary ladder:

"The government was too civilized to put men to death for subversive activities, and too cowardly to let them remain alive and at large. The compromise was the living death of Hawksbill Station. A billion years of impassable time was suitable insulation even for the more nihilistic ideas." (36)

Come to the year 2029 and the population of the primordial prison stands at one hundred forty with one-third of the prisoners succumbing to their personal psychoses. Barrett has become the leader of the chronologically desolate gulag, one who organizes men to scout for mis-shipped crates of food and materials. Losing the full mobility of his legs due to an avalanche, Barrett has become more steadfast in his hopes for the Cambrian colony, a desire which supplants his treasonous aim of governmental reform. After a six-month absence of new prisoner arrivals, a stranger arrives at the camp. A self-pronounced economist with little more to say than a simple nod and a notably empty reservoir of knowledge regarding economics and political resistance, little warning signs are piquing the accusatory eye of Barrett.

Hawksbill Station has a very similar theme to Brian Aldiss's Cryptozoic, where Silverberg's was published in 1968, Aldiss's was published in 1967. Silverberg's novella Hawksbill Station was published in August of 1967 while Aldiss's was published in October. Which author was the first to pen the idea of a totalitarian government with time travel to primordial earth (Silverberg = late Cambrian / Aldiss = pre-Cambrian)? There are obvious similarities but also drastic differences.

There are two parts to this story which capture my imagination: the penal servitude in the desolate past (draw comparisons to Dostoevsky's Memoirs from the House of the Dead or Solzhenitsyn's The Gulag Archipelago) and the form of government Silverberg calls syndicalist capitalism (as a registered Socialist, of course it would interest me). However, neither are described to a great degree and merely serve as a backdrop for the existence of temporally distant political gulag. Exactly WHY this sort of prison is BEST for the prisoners is left untouched (besides the single paragraph explanation above). And the descriptions of the barren lands of the late Cambrian period are glanced over, mentioning some soil here, lots of rock everywhere, and the expansive ocean just over there.

The actual Hawksbill Station plays second fiddle to the tribulations of Barrett. The novel alternates chapters from life at the Station and the rise of Barrett's career as a dissident. His shallow relationship with his girlfriend is a mere footnote of interest, as all female characters in Silverberg novels tend to be. Barrett's almost feigning interest in the revolution doesn't draw him out to be the powerful type, but his ability to handle interrogation, detention, ans sensory deprivation are admirable. Regardless of this, he is still sent back in time to live the remainder of his life on the expansive flats of volcanic rock, a home which he will reign as king over troglodytes and treasonous male revolutionary castaways.

A minor gripe in Hawksbill but my main gripe with the author (but noteworthy because of its recurring nature in everything Silverberg has penned) is his treatment of women as characters... or as cows: things to name and forget about minutes later, or as objects: things to place in the plot as mentions of rape (three times) and breasts (four times) can be wantonly written into the story (to garner interest from teenage boys?), or as a catalyst for excitement: pheromone-laden hussies to give climax to the plot (and conveniently, to the men, too). Call it his spice to every plot or his twist to every story, but it's the main reason I don't willingly read ANY Silverberg. Again, to say that Hawksbill is the BEST thing Silverberg has ever written is to say that everything else he has written in on par with or below a three-star rating, in my opinion.

With my gripe complete and my review of Hawksbill finalized, I can put to rest your (pointing the finger) one hope of turning me into a Silverberg fan. Sorry... but you have to admit that the plot synopsis I provided it quite good!

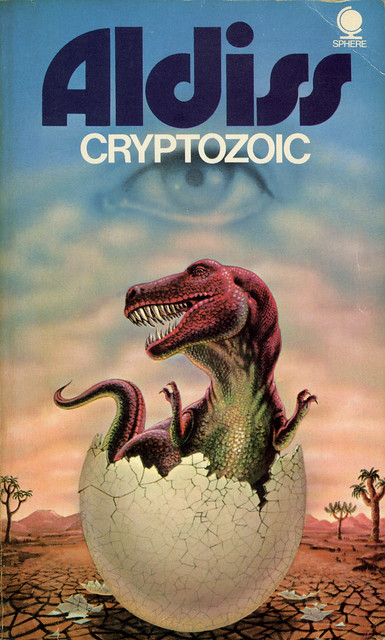

1967: Cryptozoic! (Aldiss, Brian)

Chronological and Psychological mind blow (4/5)

From July 12, 2011

My eighth Aldiss book to-date and I haven't been disappointed in any of his novels yet (while the collection in The Saliva Tree was great, the other two of Last Orders and The Book of Brian Aldiss left something to be desired for). Cryptozoic is pretty trippy, more so than Earthworks. But why else would you read Aldiss? He's got BIG ideas! Cryptozoic was originally titled An Age and was serialized in three parts from October to December 1967.

Rear cover synopsis:

"Mind-travel through the time-entropy barrier is the perfect recreational escape. It's expensive, sometime dangerous, but always fascinating. Edward Bush has travelled millions of years through the earth's primordial past, sketching the strangely beautiful landscapes of the Devonian and Jurassic ages. New he is searching the past for a man the dictator wants eliminated. And when he finds that man, Edward Bush will be hurtled across eons, against the flow of time. Waiting for him at world's beginning, in the violent cauldron where no life exists, is a future that mankind could never have foreseen... the utterly alien horror of time uncreated."

The word "cryptozoic" is hard to type out. Also, it's kind of hard to figure out. Near the end of the twenty-first century, time travel via the mind became a reality. The body would stay in 2093 but the mind would whiz back to the Jurassic era, Devonian era or even the Holocene epoch if you've got the talent. Prohibitively expensive, mind time travel is reserved for vacationers wanting to visit the mind-colony in the Jurassic era or ride their mind-motorcycles through the ages. More importantly, a research institute sends scientists or artists out to view and record the landscape of history, however, interaction with the environment is impossible.

Bush is the man we view this pan-chronological world through... from land-walking fish, to tyrannical lizards of yesteryear and to his modern day dystopia where America has crumbled and is now under leadership after leadership of tyrannical generals. Bush is a victim of Freud's oedipus complex: he's fixated on his mother and not on the best of terms with his father. When Bush learns of his mother's passing away, he joins his father in drinking binges even though he know at his father's frail age, the hooch will eventually kill him (half of the oedipus complex). Incest is a running theme though never actually consummated. This is definitely a chronological and psychological mindblow.

All goes very well for most of the book. The second half sees Bush go through military training to become a time-assassin and things get even more weird thereafter. You've really got to hunker down and concentrate on the mind time-traveling... Bush jumps to the immediate past of his own present and stops an action which is in action during his old present (umm, anyone get that?). Further into the last half, there are some more ongoings which really challenge your grip on the English language when it comes to the NOW, the PAST, the FUTURE and FATE. It's a big idea and it's pretty hard to grasp - but if you do, it's very rewarding!

5-stars for the mindblow but subtracting 1-star here for the internal logic of Bush which goes missing in the pages. Alliances change on his side and the "other" side, he was against him and now he's for him, and why exactly was he in training? Just a bit of the book is sketchy like this, but pick it up and read it for the big ideas!

From July 12, 2011

My eighth Aldiss book to-date and I haven't been disappointed in any of his novels yet (while the collection in The Saliva Tree was great, the other two of Last Orders and The Book of Brian Aldiss left something to be desired for). Cryptozoic is pretty trippy, more so than Earthworks. But why else would you read Aldiss? He's got BIG ideas! Cryptozoic was originally titled An Age and was serialized in three parts from October to December 1967.

Rear cover synopsis:

"Mind-travel through the time-entropy barrier is the perfect recreational escape. It's expensive, sometime dangerous, but always fascinating. Edward Bush has travelled millions of years through the earth's primordial past, sketching the strangely beautiful landscapes of the Devonian and Jurassic ages. New he is searching the past for a man the dictator wants eliminated. And when he finds that man, Edward Bush will be hurtled across eons, against the flow of time. Waiting for him at world's beginning, in the violent cauldron where no life exists, is a future that mankind could never have foreseen... the utterly alien horror of time uncreated."

The word "cryptozoic" is hard to type out. Also, it's kind of hard to figure out. Near the end of the twenty-first century, time travel via the mind became a reality. The body would stay in 2093 but the mind would whiz back to the Jurassic era, Devonian era or even the Holocene epoch if you've got the talent. Prohibitively expensive, mind time travel is reserved for vacationers wanting to visit the mind-colony in the Jurassic era or ride their mind-motorcycles through the ages. More importantly, a research institute sends scientists or artists out to view and record the landscape of history, however, interaction with the environment is impossible.

Bush is the man we view this pan-chronological world through... from land-walking fish, to tyrannical lizards of yesteryear and to his modern day dystopia where America has crumbled and is now under leadership after leadership of tyrannical generals. Bush is a victim of Freud's oedipus complex: he's fixated on his mother and not on the best of terms with his father. When Bush learns of his mother's passing away, he joins his father in drinking binges even though he know at his father's frail age, the hooch will eventually kill him (half of the oedipus complex). Incest is a running theme though never actually consummated. This is definitely a chronological and psychological mindblow.

All goes very well for most of the book. The second half sees Bush go through military training to become a time-assassin and things get even more weird thereafter. You've really got to hunker down and concentrate on the mind time-traveling... Bush jumps to the immediate past of his own present and stops an action which is in action during his old present (umm, anyone get that?). Further into the last half, there are some more ongoings which really challenge your grip on the English language when it comes to the NOW, the PAST, the FUTURE and FATE. It's a big idea and it's pretty hard to grasp - but if you do, it's very rewarding!

5-stars for the mindblow but subtracting 1-star here for the internal logic of Bush which goes missing in the pages. Alliances change on his side and the "other" side, he was against him and now he's for him, and why exactly was he in training? Just a bit of the book is sketchy like this, but pick it up and read it for the big ideas!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)